All Citizens: A Look at Suffrage

/The Right to Vote

What is Suffrage?

Suffrage is the right to vote. 2020 Marks the 100th Anniversary of the passage of the 19th Amendment. It has only been 100 years since women fought for the right to vote and be able to express their choice in governmental leaders.

What is the Difference Between Suffragettes and Suffragists?

The difference between suffragettes and suffragists is noted mainly in their ways of promoting voting rights, although both advocated universal women’s suffrage.

The term “suffragist” refers to the members of the women’s groups who fought for the right to vote. But, this doesn’t only a term describing women in favor of equal voting rights, but all those who were in support of the cause.

The term “suffragette”, on the other hand, is used to describe female members of the movement who fought for women’s suffrage. In short, suffragette had a narrower meaning, referring only to women.

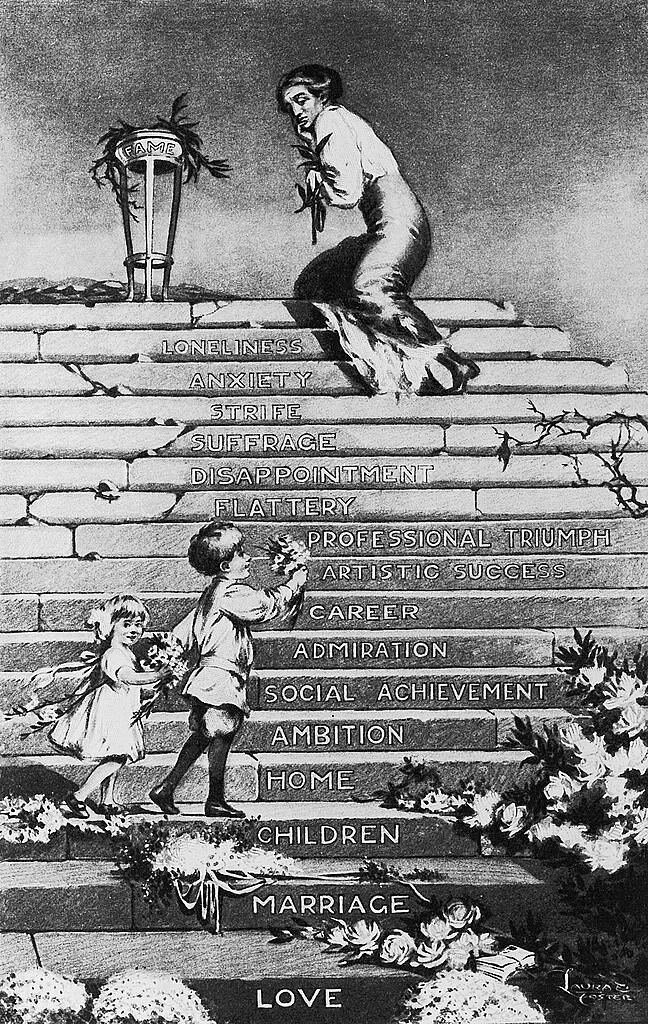

"Looking Backward." Artwork by Laura E. Foster, c. 1912. Published in Life Magazine, August 22, 1912. From the collections of the Library of Congress (https://www.loc.gov/item/2002716765/).

On a side note in 1906, a British reporter used the word “suffragette” to mock those fighting for women’s right to vote. The suffix “-ette” is used to refer to something small or diminutive, and the reporter used it to minimize the work of British suffragists.

Some women in Britain embraced the term suffragette, a way of reclaiming it from its original derogatory use. In the United States, however, the term suffragette was seen as an offensive term and not embraced by the suffrage movement. Instead, it was wielded by anti-suffragists in their fight to deny women in America the right to vote.

The history of suffrage is not a quiet story. It is not women being a picture of demure Victorian ideals. It is women using their voices and standing up for their beliefs, demanding their voices be heard by our government. In 1848, Elizabeth Cady Stanton wrote the Declaration of Sentiments. This documented the grievances against men, including:

Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815–1902). “Declaration of Sentiments,” Report of the Woman’s Rights Convention, Held at Seneca Falls, New York, July 19 and 20, 1848. Printed by John Dick. Rochester, NY: The North Star office of Frederick Douglass, 1848. Elizabeth Cady Stanton Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress (007.00.00)

“He has compelled her to submit to laws, in the formation of which she had no voice”.

“He has made her, if married, in the eye of the law, civilly dead”.

“He has created a false public sentiment by giving to the world a different code of morals for men and women, by which moral delinquencies which exclude women from society, are not only tolerated but deemed of little account in man”.

Slowly, rights were granted to women, but not because they passively waited for them, but because they refused to be silent. Suffragists challenged the notion that women needed men to care for them. They defied men's expectations that women were too fragile for political discussion and thought. Sojourner Truth’s speech from 1850 shows anything but fragility.

“That man over there says that women need to be helped into carriages, and lifted over ditches, and to have the best place everywhere. Nobody ever helps me into carriages, or over mud-puddles, or gives me any best place! And ain't I a woman? Look at me! Look at my arm! I have ploughed and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me! And ain't I a woman? I could work as much and eat as much as a man - when I could get it - and bear the lash as well! And ain't I a woman? I have borne thirteen children, and seen most all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with my mother's grief, none but Jesus heard me! And ain't I a woman?”

Those in power did not decide one day women should have their voices heard and give them the right. Early suffragists such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony paved the way for women to talk less and act more. They gathered powerful male allies such as Daniel Anthony and Frederick Douglass who were vital to the success of the movement. Frederick Douglass wrote this after the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention:

“All that distinguishes man as an intelligent and accountable being, is equally true of woman; and if that government is only just which governs by the free consent of the governed, there can be no reason in the world for denying to woman the exercise of the elective franchise, or a hand in making and administering the laws of the land. Our doctrine is, that ‘Right is of no sex.”

In terms of using the law, one woman did and that was Ellen Martin. In fact, 29 years before women were granted the right to vote.

Lombard Town Charter, c.1869.

Ellen Martin, a lawyer, found a loophole in the 1869 Town Charter of Lombard which read "All citizens" which allowed her and other women to vote in the April 1891 election. The State and Federal government said women were not allowed to vote. The motivation behind Ellen's actions was not clear but she and the fourteen women who voted with her were not jailed for voting.

On the other hand, Susan B. Anthony would... in the 1872 election. She was arrested three weeks later for violating an act of Congress and brought before a judge in Rochester, New York. Susan's words to the man who arrested her:

“I prefer to be arrested like anybody else. You may handcuff me as soon as I get my coat and hat.”

Fifteen other women were also arrested for illegally voting. Sojourner Truth appeared at a polling booth in Battle Creek, Michigan, demanding a ballot to vote; she was turned away. Suffragists knew the risks and still protested.

Sojourner Truth, c.1864. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA.

African-American women supported the suffrage movement but were often hampered by a lack of education or by racial inequality, especially in the post Civil War Southern States. While Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth led the way for female African-American suffragists, it progressed to women such as Ida B. Wells and Mary Church Terrell. African-American women were told to be at the end of marches or were excluded from Suffrage organizations so they created their own.

Ida B. Wells was an African-American suffragist who fought for the voices of Black women to be heard. She was born into slavery but was freed by the Emancipation She graduated from Fisk University. She was a teacher but then co-owned and wrote for the Memphis Free Speech and Headlight newspaper. Her documentation of lynchings of black people by whites as a method of intimidation and economic suppression led to threats against her life. She left Memphis for Chicago.

She saw suffrage as a way for African-American women to become politically involved in their communities and to use their votes to elect African-Americans, regardless of gender, to influential political offices. She created a Women’s Club, later renamed the Ida B. Wells Club, the first civic club for African-American women in Chicago. With Jane Addams, she stopped segregation from being introduced to the Chicago school system. She created the Alpha Suffrage Club which helped African-American women register to vote and give them tools to engage in civic matters especially looking to elect African-American women into office. She clawed out space for her voice to be heard and brought all women with her.

Ida B. Wells-Barnett in a photo taken in the 1890s. (Chicago Tribune historical photo).

President Lyndon B. Johnson moves to shake hands with Dr. Martin Luther King while others look on. LBJ Library photo by Yoichi Okamoto, c.1969.

But the work of Ida B. Wells, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and other women is far from over. The passage of the 19th Amendment meant women had the right to vote, but the execution of the law was not always equal.

More to Do…

Three years after the ratification of the 19th amendment, the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) was initially proposed in Congress in 1923 in an effort to secure full equality for women. It failed to achieve ratification, but women gradually achieved greater equality through legal victories that continued the effort to expand rights, To date, thirty-seven states have passed ERA bills.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 prohibited racial discrimination, shifting the power of voter registration to the federal government. This landmark legislation passed forty-five years after the 19th Amendment codified the right to vote for all women but all was meant to give all the right to vote.

As historians, we do our best not to look at history through rose-colored glasses. History isn’t simple, it can be unjust, but it can help us today confront uncomfortable truths about society. It teaches us how belief systems were challenged and how they have been changed. The past provides a benchmark for how far we have actually come and how much further we need to go.

Citations

Pinar, William F. (2009). The Worldliness of a Cosmopolitan Education: Passionate Lives in Public Service. Routledge. pp. 77–79. ISBN 9781135844851.

Schechter, Patricia (2001). Ida B. Wells-Barnett and American Reform, 1880–1930. The University of North Carolina Press.

Grossman, Ron (June 23, 2013). "Illinois Women Win the Right To Vote". The Chicago Tribune. Retrieved November 17, 2018.

Bay (2009). To Tell the Truth Freely:The Life of Ida B. Wells. p. 4.